Reaction tools

Table of contents

Criterion: False or misleading

Facebook Third-Party Fact Checking Tool

The Third-Party Fact Checking Tool is a Facebook fact-checking program developed from December 2016 onwards. Facebook already used methods to fight disinformation, such as the removal of accounts or content that violate its policies or the provision of context to users for specific stories.

It developed several partnerships with third-party fact-checking organizations, which help Facebook in the identification of false stories. As of April 2019, Facebook had 25 partners (including the Agence France-Presse (AFP), India Today Fact Check, Africa Check Kenya, Faktisk (Norway), Teyit (Turkey) and Factcheck.org (US) ) in 27 countries (Argentina, Brazil, Cameroon, Canada, Columbia, Danemark, France, Germany, India, Indonesia, Israël, Italy, Kenya, Mexico, the Netherlands, Nigeria, Norway, Pakistan, the Philippines, Poland, Senegal, South Africa, Spain, Sweden, Turkay, the UK and the US).

These fact-checkers are independent and certified through the non-partisan International Fact-Checking Network (IFCN). They can review public or media content including links to articles, photos and videos.

Detection

Detection relies heavily on users. It can either be based on reports ( i.e. when Facebook users submit feedback on a story, claiming that it is false) or on comments (i.e. “when users comment on an article expressing disbelief”).

In the US, machine-learning is developed by using already fact-checked and reviewed articles. Detection can also be proactive, that is to say fact-checkers can identify stories to rate before being notified.

Qualification

Fact-checkers review and rate stories, then provide reference articles detailing their fact-check and reasons for the rating. Articles are shown in a “Related Articles” section just below the story reviewed in a user’s news feeds.

The rating offers on 9 options:

- False: when the content is factually false

- Mix: when it is a mix of exact and false information / when the main claim is false or incomplete

- Misleading title: when the main claim of the article is factually true, but not the main claim of its title

- True: when the content is factually true

- Ineligible: when content can’t be verified, or when claims were ture when they were redacted, or when content is coming from a site or webpage that specifically diffuses the opinions or the program of a political personnality

- Satire : when the content is explicitely enough satirical

- Opinion

- Hoax generator: when a website allows users to create their own hoaxes and share them via social media platforms

- Not evaluated : when the content has not been reviewed yet or cannot be evaluated. It can also be used when fact-checkers deem that no measure ought to be implemented.

Reaction

Fake accounts, tools often used to spread disinformation, can be removed.

Once reviewed, false content is demoted and it is shown lower in the news feed, which means that its visibility is reduced - by over 80% on average. Facebook also provides more context to its users. People who try to share a false story as well as previous sharers are notified of “more reporting on the subject”.

A Facebook page or a website that repeatedly shares misinformation are sanctioned: their visibility is reduced and they can no longer make money or advertise on Facebook.

It is possible for editors and publishers to challenge a decision, in which case they can directly contact fact-checkers “to dispute their rating or offer a correction”.

ClaimReview markup

ClaimReview can be described as a specific type or format of fact-checking review. It focuses on claims made or reported in creative work. Among properties of a ClaimReview are the claim reviewed, its rating and its aspect (part of the claim to which the review is relevant), along with the review itself. It was developed by the collaborative entity Schema.org, of whom companies such as Google and Microsoft are founders.

A ClaimReview markup is thus a sort of beacon, a tag, which recognizes the ClaimReview format. It indicates to machines what humans can see, which is whether an item is a fact-checking article or not- and therefore whether a claim has been verified.

Such reviews, i.e. ClaimReview structured data, can be included in one’s fact-checking web page or site independently, or through Google’s Fact Check Markup Tool.

The Fact-Check Markup Tool

This Google tool allows fact-checkers, journalists and publishers to easily add a ClaimReview markup to their fact-checking articles. This is also possible without using the tool, however the structured review has to be embedded in the code of the article, which can be too technical a process for some actors.

With the FCMT, a summarized version of a fact-check can be displayed in Google Search results along with the fact-checker’s page. Indeed, search engines will be able to recognize said page as (hosting) a fact-checking article. In this summary are included the nature and author of the claim and a brief assessment of its truthfulness, among other data.

Any fact-checker can add and edit ClaimReview markup to its articles, however one cannot review its own claim. To create markup, one has to be registered with a Google account email address and use the Google Search Console. The account must be listed as a restricted user or full user of the site it wishes to create markup for.

In order to use the FCMT, publishers have to indicate, on top of the ClaimReview itself, a link to their fact-checking article on their site or page, a summary of the assessed claim and their rating.

PolitiFact, Snopes, Le Monde, France Info, FactCheck.org, The Washington Post and AFP Factuel all use the FCMT. Therefore, their reviews are displayed on Google’s FCE.

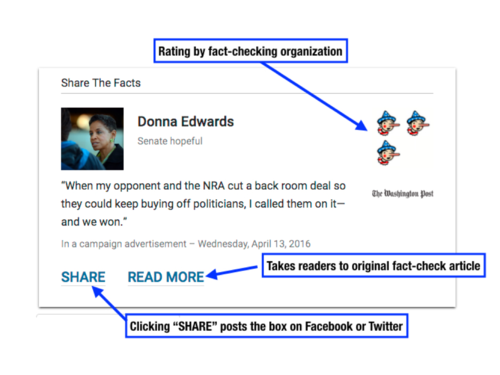

Share the Facts

Share the Facts is a widget that makes it easy to share fact-checks on social networks by providing an embeddable, standard user interface summing up claims and ratings by partner fact-checkers.

In France

Datagora

On this website, “datapoints” are published almost daily and classified in relevant topics (Economy, Politics, Society, Environment, International), themselves divides into subcategories. These points can be articles, graphs or even videos. Logging into an account is not required to access information.

These datapoints can be embedded in any website, making it easy to write fully-sourced, data-backed responses with appealing graphics.

Criterion: Intent to harm

Content takedown

In France

PointDeContact.net

Point de Contact is an association partially funded by EU Member States and institutions. The association was created in 1998 and is supported by French public and private actors, as well as by the European Commission.

Its online platform allows webizens to report (potentially) illicit digital content online through a form, by first selecting the nature of the offense in a list, then describing it and ultimately sending the URL of the content through the website’s portal. It deals with pedopornography; terrorism or bomb-making incitement; suicide incitement; violence, discrimination and hate speech; and procuring. PointDeContact offers a detailed explanation of each category, thus participating in an education effort for the civil society on Internet content.

PointDeContact directly analyzes reports received through its platform. The latter belongs to the « Safer Internet Centre Français» (French Center for a Safer Internet) alongside “e-enfance” (another association, with a hotline) and “Internet Sans Crainte” (an awareness service).

PointDeContact co-founded the Inhope network, a hotline services network operating worldwide.

PointDeContact members, like Google and the French Ministry of Interior, are also its operatives.

PHAROS

Pharos is the official portal of the French Ministry of Interior for online illicit content reports. Webizens can anonymously (or not) report shocking content through a form. The website also displays advice and information, and offers a Q&A section.

Reports are stored for ten years in the Pharos database before being erased. It is possible to send a report at any time, however they are not processed at night, on week-ends or during holidays, which means that content that requires immediate intervention shouldn’t be reported through Pharos.

Legislation

Some countries, like Switzerland, have decided that the fight against disinformation was not a priority. However, several states have taken measures and implemented laws to counter the spread and effects of disinformation on their soil.

France

A law going back to July 29, 1881 (revised since) regarding freedom of the press already condemns the “publication, diffusion or reproduction, by any means, of fake news, pieces that are fabricated, falisfied or falsely attributed to third parties when, made in bad faith, it disrupted public peace or could have done so” to a 45 000 euros fine.

Germany

The NetzDG law (Netzwerkdurchsetzungsgesetz, literally “law on implementation / enforcement for networks”) passed on January 1st, 2018. It aims at fighting hate speech and disinformation on social networks. Platforms are obligated to remove such content once it has been reported. They have from 24hours up to a week to do so, depending on the obviousness of the falsehood or of the illicit character of the content.

If they do not comply, platforms must pay a fine of maximum 50 million euros, with possible individual fines of up to 5 millions euros for platforms leaders.

Kenya

On May 16, 2018, a law against cybercrime and cyberbullying was passed, which condemns - among seventeen cybercrimes - the publication of “false, misleading or fictitious data” to a fine of 42 000 euros and/or a two-year prison sentence.

Indonesia

Since January 2018, webizens who publish fake news face a prison sentence of up to six years.

Italy

Through a website, citizens can report potentially false information to the police. A specialized police force for communication is in charge of verifying or fact-checking reported news, and must publish a statement of denial in case it is proven false. It is then possible for this police force to bring the case to judiciary authorities.

Russia

In March 2019, two laws were passed to fight disinformation on the Internet and especially social media.

The first one is aimed at “socially significant false information that are spread as true information” and constitute a “threat to public or state security” or may cause “massive disruptions”.

Platforms and online media outlets which spread “fake news” can be fined for up to 20 500 euros (1.5 million of roubles). If a media refuses to suppress what is deemed to be false information, its activity can be suspended.

However, no clear definition of what constitutes a “fake news” is given, as definition is left to the appreciation of the prosecutor, case-by-case.

The second one punishes “disrespect” toward state authorities and “offenses to state symbols” of fines and up to fifteen days of imprisonment in case of recidivism.